Steve always knew he was going to die. Not only was it a fact of life, it was a fact of his life that he was going to die young. All the doctors who came unwillingly to their door told him that. They didn’t even bother to sugarcoat it. Steve was going to die, and he was going to die soon. If it wasn’t his anemia or his asthma, it was going to be his scoliosis. Or, as one doctor had said on his way out, his one working ear would fail to hear a car and he’d get hit while trying to cross the street.

Bucky had wanted to chase that doctor down and give him a piece of his mind. Steve told him that he’d do one better: he would live. Whether it be a medical miracle or spite, he would live.

He’d had a dream once as a kid that still returned to him: huge billowing machines wafting acrid smoke, crackling electricity, people in long coats running around and yelling. A bright, white light flickering like flames. He’d woken up with the smoke still in his throat. He hadn’t told anyone about it, not even Bucky. They’d had other things to worry about. More important things. Scraped knees and soccer matches and eating lemon candy.

It also felt a lot like dying, so Steve wanted to forget about it.

Bucky gave him a lemon candy and he stuck it in his mouth, saliva already pooling at the sourness. He grinned at his best friend and his best friend grinned back. The sun shone and he was happy and he was going to live forever.

Despite needing a crutch and the fact that no one other than his ma and Bucky remembered that he couldn’t hear out of his left ear, Steve refused to let anything keep him down. He memorized the taste of blood in his mouth like it was an elixir. Bruises became steel. His body became armor that no one could pierce because no one else loved and hated it the way Steve did. It was wings, and it was an anchor.

He couldn’t run, but sitting up on the fire escape, eyes closed, night wind buffeting him—god, it felt like flying.

He wanted to run the day he learned his ma died. He stood alone at the front of the empty church, his father’s suit rumpled and overlarge, drowning on dry land. There was never a time he hated his body more, too weak to do anything but watch as the pallbearers carried her away.

Steve wanted to run the night Bucky got drafted. He made it as far as the steps of their apartment before gravity dragged him down. Bucky sat next to him. Steve rested his head on his shoulder, deaf ear up. If the world ignored him, why shouldn’t he ignore the world?

Steve always knew he was going to die. There’d been too many nights he shivered with fever, too many days went without food, too many days he sat petrified that he would die without having a choice in the matter. If he was going to die, Steve wanted to have a say. If death would know him no matter what, shouldn’t he have a choice?

It was one of the only things he and Bucky argued about. The first time Bucky found his application, he’d made sure Steve’s right ear was toward him. Growing up together since they were toddlers, they’d developed their own language. A mixture of sign language, his ma’s Irish, and the Barnes’ Yiddish. There was nothing in their blended lexicon that could express either of their feelings.

Desperation in two folds. Tired acceptance and blistering anger.

They were both going to die, and they knew it. Steve fished a lemon candy from his pocket and handed it to Bucky. He laughed softly and shook his head. Warm, dry skin brushed against Steve’s palm as he grabbed it. It tasted like sunshine and scraped knees and a child’s hope.

The first time Steve remembered the dream was the night Dr. Erskine asked if he wanted a chance.

“If I’m going to die anyway,” he said to Bucky later that night as they lay in their bed. Their apartment was lit by nothing but a slice of moon. The skin of Bucky’s shoulder gleamed in the silver light. “I want to at least have the chance to save you.”

Bucky’s breath ghosted over Steve’s face. The springs creaked as he turned over, away from Steve. “Don’t.”

When he woke up, Bucky was gone. A lemon candy sat on his pillow.

Steve tried to run. He ignored the sharp pain in his flat feet and the gasping of his lungs and the crutch digging into his armpit. He ignored the stares of people watching him, the murmurs and mutters that seemed to enter even his deaf ear. Steve ran the way he’d been running his whole life. Towards fights and away from death.

His shoe caught a rock and for a moment he really flew. Steve closed his eyes, feeling the wind against his skin. For a moment, nothing else mattered. The pavement met him with eager arms, scraping his skin and watering the concrete with flecks of his blood. He lay there, his cheek pressed against the sidewalk, his eyes closed. His head pounded with the beat of his heart. His throat ached with the burn of unshed tears and the remembered tang of smoke and lemon candy.

Steve pushed himself to his feet and walked back home.

“We call it Project Rebirth.” A short man with slicked-back hair walked with him. Goggles sat on top of his head. Steve vaguely remembered him from the Expo. A car promised to fly. Bucky had been so excited to see it. Howard.

“Officially, this project doesn’t exist.” The words were muffled. A woman came up on his left side. Peggy. Her hair was perfectly curled. She kept talking. Steve read her red-painted lips. Experiment. Super Soldier. Everything Erskine had told him before.

A door behind a faux wall opened and for a moment, Steve was back in his dream. A large machine sat in the center of the room. There was no smoke, but it still smelled. Antiseptic. Clean. It bit his nose with its sharpness.

Howard said something and hurried down the stairs, leaning over the shoulder of another man and pointing something out. Eventually, he pushed the other man away and typed himself. Steve didn’t want to think of what that meant. The woman spoke again. Steve turned his head but still only caught the last of her words.

He followed her down the stairs, where two nurses immediately rushed over to him. One strapped a pressure cuff to his right arm. Steve finally caught sight of Dr. Erskine, who shooed the women away.

“You still have time to back out,” the doctor said, his mouth close to Steve’s right ear to account for the cacophony around them.

Steve remembered soccer matches and scraped knees and the happiness brought by lemon candy. He remembered Bucky leaving without saying goodbye.

“No.” Steve set his crutch down. “I’m here.”

Steve was going to save his best friend.

Dr. Erskine stared at him for a moment. Steve stared back. The doctor nodded.

Even decades later, Steve would never forget the serum entering his veins. It was fire and ice. His blood boiled and his skin burned. Light blinded him. Someone screamed in pain. It echoed, blending with the consuming fire. He wanted to run. He didn’t care if it was toward death. Death would be better than this.

As kids, he and Bucky had sleepovers. Steve made Bucky tell him ghost stories. The Headless Horseman, hearts in the floor. A man with a hook for a hand. He’d felt his heart beating in his chest, goosebumps raising along his arms as Bucky wove the tales. Steve always pretended he wasn’t scared.

One second stretched into eternity. Ice replaced the heat, but it didn’t bring relief. It burned just as much. Where the fire had spread rapidly, the ice moved glacially slow.

Eternity. The blink of an eye.

Smoke billowed when the doors of the machine opened. It sat in his throat.

In the tent at the Expo, Dr. Erskine had given him an offer. They’d called it Project Rebirth because the person was supposed to be reborn. Steve was supposed to be a phoenix. He was supposed to rise from the ashes of his old body, leave behind his deafness and his limp and the scoliosis that bent his entire body to the left. He was supposed to leave behind everything that held him back.

There was silence.

The moment he’d been strapped into the machine, sharp, hot pain had sliced up his crooked spine. When they closed the doors, Steve dreamed of the moment the pain was gone. He dreamed of the moment he could take a deep breath without struggle.

Dr. Erskine took a step forward. Howard slipped his goggles off his head and set them on the control panel.

Steve never told Bucky how those stories scared him. How he’d had dreams of hearts beating beneath his floorboards, how he’d imagined a headless man on a horse lurking beneath his window at night.

Steve thought he’d known fear, just like he thought he’d known pain.

He’d been wrong.

The pain was worse now that it was mingled with oversensitive skin and overstretched senses. Someone spoke to him. His right ear rang with a high-piercing screech. His left ear was dead.

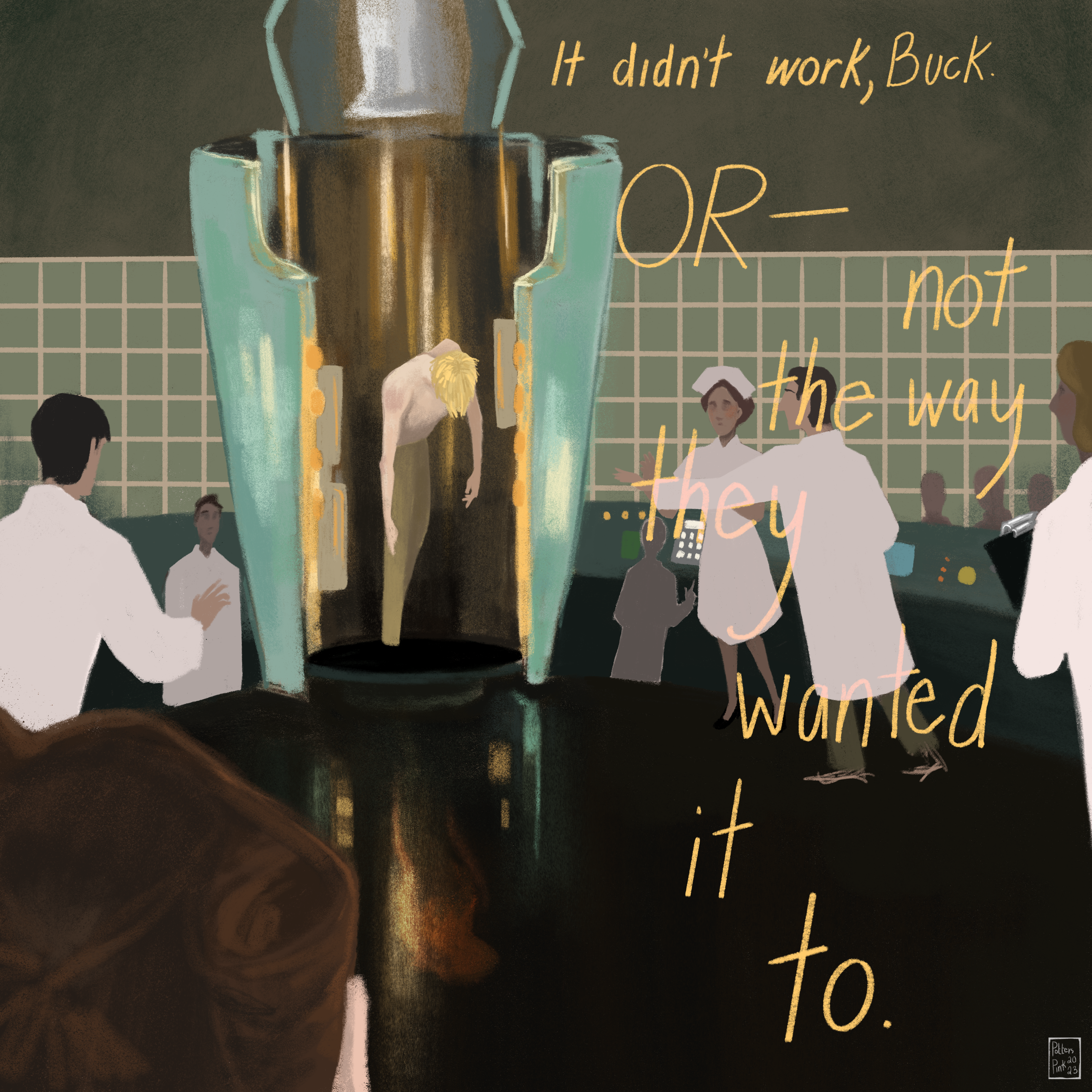

It hadn’t worked.

They ran a series of tests. Tens. Hundreds. Steve lost track.

You told me not to do it, Steve wrote when he was alone at night. They hadn’t let him go home yet; there was still too much unknown about the serum’s effects. If there’d been any. The room they gave him was stark. A plain bed with hospital corners. Dreadfully white walls. Empty. Soulless.

You told me it was stupid, offering myself to be a medical miracle. But I really thought it would work, Buck. I wanted it to work. I wanted to be better than I am. I wanted to be able to save you.

Steve offered his arm and they drew blood. They tested his reflexes, his eyesight, his hearing. Nothing had changed.

Steve hated doctors.

They don’t know why it didn’t work. Maybe it’s me. Maybe I was too much for it. Maybe I am too much to fix. Maybe everyone else is right. Maybe I am just supposed to die.

Erskine came and spoke with him most nights. Steve knew he was trying to be kind, to make it seem like he still mattered, that there was a reason he took up valuable resources. Steve tried to listen, but there’d only been two people who’d ever been able to pierce through his anger.

One of them was dead. The other he was supposed to save.

I miss you, Buck.

Steve’s entire life, he’d been running away from death.

At least I’ll have a story to tell when you come home.

He remembered the feel of pavement beneath him. The sting of scraped skin and the ache of knocked bones. He remembered a young boy with a missing front tooth and curly hair sticking out his hand to help him up.

You better not die, you asshole.

There was no hand now. It was only him and the pavement and the hounding tick of the clock.

They let him leave eventually. His skin still itched and sometimes at night he felt his blood boil, but he was no longer of any use to them. The government paid him for his discretion. Steve didn’t know what he’d do with the money. He hated the way it felt in his pockets.

His apartment was nothing more than a shoebox. A kitchen he could barely turn around in, a ratty couch, and a bed. The window barely opened. Some nights, it felt like the entire world fit inside. It felt smaller without Bucky taking up space.

Shadows drew long across the walls. The door should’ve been opening. Bucky should’ve been coming home smelling like the docks. Like salt water and sweat and oil. No matter how bad the day, Steve would’ve laughed at something he said.

Steve turned around, staring at the peeling paint and crooked floorboards and hissing radiator. When they first started living together, every night was a sleepover. Curled in the same bed, they told ghost stories and the radiator would rattle and the floorboards would creak, and Bucky would call them ghosts.

Bucky was the ghost, now. There were imprints of him everywhere. A cigarette stub in the window, a pulp novel open on the couch, his shaving cream on the bathroom sink. Steve hadn’t realized just how much he’d become part of the foundation.

There was his life before Bucky and his life with Bucky. Steve didn’t want there to be an after.

He hated the last words that rattled in his head. Steve shouldn’t have been hoping for a miracle when he’d already had it. He’d wanted the serum to save him, to make him worth something, to make him more than he was. He’d been so desperate for it, he’d tasted it.

It was nothing like lemon candy on a bright, summer day.

Steve shouldn’t have been hoping for a miracle when he’d already had it.

He closed his eyes and took a deep breath. The radiator hissed. He felt the creak in the floorboards more than he heard it. The serum still itched in his veins. His lungs ached. He’d always complained about it at night. Bucky refused to look up from his book to say, “we all got somethin’, Stevie. That’s how you know you’re alive.”

Steve had hated it. He hated the way everything always ached, hated how much energy it took just to breathe and walk and survive. He hated the way his ribs stood against his skin. It was easier as a kid when Bucky was just as gangly and unfinished. It was easier to forget and breathe through the ache and taste the smog of the city air.

Even when Bucky had grown into his body, when gangly youth had transformed into graceful angles, it had been easier than this, because he’d still been here. Steve had been able to reach out and touch him and Bucky would laugh and Steve would laugh and for a little bit, it would be okay.

Steve had never needed to be alone before.

Bucky had been quiet the week leading up to his deployment. He hadn’t understood why Steve was so desperate to throw himself into battle when the thing he wanted more than anything was to live a normal life. He wanted to save enough money to go back to school, find a girl, start a family. What he wanted, he told Steve, was quite simple. He wanted to live.

Steve never had the luxury of thinking ahead.

Maybe it was a blessing the serum didn’t work.

Maybe it would be enough just to live.

Dr. Erskine visited him once a month later. Peggy came with, sitting on the couch Bucky had always occupied. She offered him a place in the SSR, behind the scenes but still part of the war effort. A good job with good money; that’s what Peggy said. Access to the best doctors and medicine. A purpose beyond a failed experiment. Her voice and face were kind.

Erskine told him they were doing more tests on the serum, trying to figure out what was wrong. He wanted to know if Steve would try again. Out of everyone, he was still their best candidate. Something to do with his heart and his kindness.

The serum itched in his veins. Bucky’s voice pleaded in his ear. The empty bed and the absence of a goodbye seared him. Don’t. Don’t follow me and die. Goddamit Steve, just take what you have. Don’t you realize what I’d give to stay? Don’t make me come home to a stranger. Don’t.

Steve watched them leave. Peggy looked back once as she walked down the stairs, sorrow twisting her features. He almost invited her back, if for nothing but to not be alone.

He shut the door.

Steve learned how to be alone. He made himself live the life Bucky would’ve wanted. With the money he’d been given, he went to art school. It was nice being in a room with other artists. Sometimes, the girl next to him leaned over to ask how he made his brushstrokes so smooth. He walked the streets he used to frequent, a portfolio under his left arm. The weight of it kept him from searching for fights. The drive wasn’t there anymore, with no one to pull him out.

Every night, he wrote a letter. Sometimes, it was a word. Sometimes, it was pages. Sometimes, it was smudges of charcoal, a spatter of dried tear stains, and the perfect circle of a cigarette burn.

1944.

Winter had finally warmed into spring when there was a knock on his door. Steve pulled himself away from his canvas and opened it to find Peggy standing outside, her arms crossed over her chest. Her hair was still perfectly curled, her lipstick bright red and unsmudged.

“Can I come in?” she asked when Steve just stood there. He’d never expected to see her again. Why should he, after he’d turned down her offer?

Sometimes, Steve wondered what it would’ve been like had he agreed. Would he be in a different apartment, one that had heat so he didn’t shiver through the night? Would doctors actually see him, or would they still scorn him and turn him away?

Steve stepped back, and she walked past him to sit gingerly on the couch. Bucky’s spot. Words died on his tongue. There was nowhere else to sit unless he dragged another chair from the table. Even if he did, Steve didn’t know where he’d put it. He’d already moved the other chair in front of his easel. They’d only had two.

Peggy looked around, her eyes flitting from the peeling paint to the crack in the window pane to the new canvas he was working on. Steve had just finished the underpainting. Bucky stretched out across the couch, his eyes closed, a small, content smile on his lips. It was how Steve liked to remember him. When he woke up from nightmares of him in the trenches, he remembered those nights. He remembered their laughter. Those were some of the nights Steve felt most alive.

He shifted on his feet, placing more weight on his crutch. “Did Erskine send you?”

“No,” Peggy said. “No one knows I’m here. For all they know, I’m getting lunch.”

“Then why did you come? I thought I made it pretty clear I wanted nothing else to do with this project.”

Peggy swallowed and brushed non-existent hair from her forehead. “You did. I wanted to see how you were doing. This winter wasn’t easy, even for—” She stopped, her eyes flickering so quickly to Steve’s crutch and back that he would’ve missed it had he not been trained to watch.

Steve didn’t bother finishing her sentence. The winter had been harder than usual. War and snow and bitter cold. Christmas Mass had never felt as important. He’d felt the pipe organ in his bones.

It was the first winter he hadn’t gotten sick.

The serum still itched in his veins. Steve didn’t know if it was real anymore.

“I don’t need anyone to check up on me. I’m fine.”

Peggy’s brows furrowed slightly. “I didn’t mean—Steve, I’m not here because I care about some serum and whether it worked or not.”

“You wanted it to, though, right? You wanted to see me as some hero because if it worked for me, it would work for anyone.” He wanted her to yell back. It’s what Bucky would’ve done. Bucky would’ve told him to get his head out of his ass and screwed back onto his head. Not everything was about him.

His fists ached to hit something. His right ear longed to hear Bucky’s footsteps a moment before he came into view to drag Steve away. The radiator hissed.

Peggy stood up and walked towards the door. “I’m sorry I came. I obviously shouldn’t have.” Her heels clicked on the hardwood, melding with the creaking of the floorboards. It was different than what he was used to, but the sound quieted something in his mind. He wasn’t alone anymore.

“Peggy, wait,” he said. She didn’t turn. “I’m sorry. I’m—” He licked his lips. They were chapped. “Hell, I don’t even know.”

Peggy turned around. “You miss your friend,” she said, nodding towards the canvas.

Steve nodded. His crutch dug into his armpit and his feet ached. Bucky would tell him to sit down. He kept standing. “He didn’t want me to take the offer,” Steve said. “Bucky didn’t want me to follow him into a war he didn’t want to fight.”

Peggy sat back on the couch.

“That was where he always used to sit,” Steve said. “Every night when he came home from the docks, he’d sink right down. I’d always tell him that one day, he’d sink right down to the floor. He always said that was the goal because then he’d never need to leave.” Steve swallowed and bit his lip. He looked at the canvas.

“Ever since we were kids, we always said we’d follow each other until the end. We both knew I’d die first. There was never any debate on that. Not till now. Some nights, I think he wanted to prove a point that I didn’t have to die first.”

When he’d first been released from the SSR, he went over to the Barnes’ apartment. Winnifred had opened the door, her hair tied up in a tichel. George and Becca had been playing cards at the table. Everything had seemed so normal until Winnie had said an extra prayer over dinner and he’d heard Becca crying under the stairs before he’d left.

“I’m sure that’s not true, Steve.”

Steve pulled his gaze back to meet hers. Her eyes were brown, earthy and warm. Far different than the stormy sea of Bucky’s. Steve had once spent an entire afternoon trying to get the right color. He still hadn’t.

“I know.” His back ached.

He kept standing.

1945.

Time didn’t make it easier, but it passed.

Peggy visited until she was called back to Europe, and Steve found he missed her company. She didn’t make him laugh as much as Bucky, but she’d learned to make sure his right ear was turned toward her and that he loved to paint with green despite not really being able to see it, and she was someone to talk to.

Steve went to school and made art and sometimes went to Shabbos dinner at the Barnes’. It wasn’t the same without Bucky sitting beside him, his voice low and smooth as he participated in the prayers he’d known since birth.

Steve knew something was wrong when he opened his door to find Winnifred. He immediately stepped back to let her in, where she busied herself making them tea despite Steve’s protests.

When Steve was a boy, he’d pushed himself past his breaking point. He’d wanted to prove that he was like everyone else, that his limits were able to be pushed. His ma had knelt in front of him, closed her hands over his, and quietly asked him to stop.

Steve walked over to Winnifred, closed his hands over hers, and asked her to stop. She looked up at him, her eyes wide and shadowed with grief. Her hands shook inside of his.

“Tell me,” Steve said.

“We got a letter,” she whispered. “Jamie—he—”

Steve had known the moment he’d seen her. The blow hit harder than he’d ever imagined it could. It was supposed to be him. It was always supposed to be him.

“How?”

Winnifred swallowed. The small act seemed to give her the courage needed to finish. “There was a train accident. There was no body to recover.”

The mundane nature made it all the worse. A train accident. That could happen anywhere. Anytime they took the subway to Coney Island. They took it all the time. All it cost was a nickel and they could go anywhere. (Some days, it had felt a lot like flying.)

“He gave his tags to someone in his unit.” Winnifred still spoke. Steve made himself listen. She pulled her hands out from between his and took something from around her neck. The metal was cold against Steve’s skin when she pressed it into his palm.

“Winnifred, I can’t,” Steve said. He could feel the engraving on the metal. Steve closed his hand tighter around the tags, wanting nothing more than to have Bucky’s name forever carved into his skin. Proof that he’d lived. Proof that Steve had loved him.

She looked him straight in the eye. “He loved you, Steve. He would’ve wanted you to have them.”

“He loved you, too.”

Her smile was tight-lipped and lined with grief. She patted his cheek and walked toward the door. “Take care of yourself, Steve. Come to dinner every once in a while. Our door is always open for you.” She patted his cheek again and left.

Steve remained standing in the doorway, Bucky’s name pressed into his palm, feeling strangely relieved knowing he hadn’t been the one to die first. Guilt followed, and then the familiar, pressing wave of grief. He closed the door and grabbed the lemon candy from Bucky’s pillow. He sank to the floor, not caring he would struggle to get back to his feet. Bucky always told him to sit down.

His tears never came.

The radiator hissed. The floorboards creaked. Bucky had always called them ghosts.

One night, when they’d been kids, Steve had told Bucky that when he died, he wouldn’t move on. He’d become a ghost and haunt Bucky because what was the point of an afterlife if Bucky wasn’t there with him?

Steve put the candy into his mouth, trying to taste the laughter and happiness of two boys in the summer sun.

Bucky had been a ghost, but he was always supposed to come back.

The candy tasted of dust and charcoal powder and the ashes of Bucky’s cigarettes.

Steve hated ghosts.

They won the war. The streets were filled with people celebrating. Soldiers came home. Steve kept waiting.

The radiator still hissed and the floorboards continued to creak.

1946.

1947.

Peggy still visited every once in a while. Over cups of tea, she told him about her new job and how she was making a name for herself. Her colleagues saw her, now. They valued her. She told him about this man she’d met, someone who also needed a crutch due to an injury in the war. She told him that she could find a place in the office for him if he was looking for something new.

Steve painted and walked the streets and sometimes stopped at the grave Winnifred had made for Bucky. On his birthdays, he left a lemon candy.

He still had the same dream sometimes, of smoke and electricity and scientists running in their long white coats. He woke up with the remembered tang of smoke in his throat and his blood itching.

1948.

1949.

1950.

Steve hadn’t always avoided mirrors.

His ma had owned a small one, and Steve remembered sitting at the table most nights, carefully rolling and pinning her hair. He would crouch behind her, his arms wrapped around the legs of the chair, and watch the practiced turn of her fingers and the flash of her reflection in the mirror.

When her hair was finished, she took him onto her lap and Steve would stare at their reflections. He’d loved how they matched. The same yellow hair and the same blue eyes and the same shape to their mouth when they smiled. Only their noses were different. Steve had his pa’s nose. Long and crooked.

Bucky had one, too. He stood over the sink and fussed with his hair before going out on dates. Steve watched him and smiled.

His ma died. Bucky went to war.

Steve hated mirrors. Hated seeing the reflection that the serum was supposed to change but didn’t. If it had, maybe Bucky would still be alive to keep fussing with his hair.

1951.

Steve still wrote letters. One per week. He kept them in a box in the oven. It hadn’t worked in years.

1952.

1953.

He’d known something was wrong for a few years. He didn’t get sick like he used to. The coughs that wracked through him every winter and the fevers that left him bed-bound and weak didn’t come.

His body still ached and he still couldn’t hear and the winter wind still sank deep into his bones, but he stayed healthy. He never expected to live this long. Steve supposed that out of everything, that was all he could ask for.

Steve couldn’t always avoid mirrors. As much as he wanted to, reflections were everywhere. Puddles in the street after a storm, shop windows, the backs of spoons. He tried not to think about what he saw.

1954.

1955.

Peggy hadn’t stopped staring at Steve since she’d let him in. He stood in front of the couch. Steve didn’t sit anymore, not unless his body demanded it of him. Even then.

Sousa stepped into the kitchen to give them privacy. Steve almost wished he’d stayed. They were less likely to say what was on their minds when her husband was there.

“Say something,” he said.

“Sit, Steve. Please.”

Steve stood up as straight as his curved spine allowed. “I need you to say something so I stop feeling like I’m going crazy. I need to know it’s not all in my head.”

Peggy licked her lips. They were stained the same shade of red as when they’d first met, but her hair was styled differently, and there were a few strands of silver. The stress of the job, she’d said. Steve knew differently. He was older than her. She was aging.

“Daniel, darling, can you bring me that file on Project Rebirth?”

Her eyes roved over Steve’s face until Sousa limped in with a file. Peggy took it from him with a quiet thanks, and he kissed her temple before returning to the kitchen. “The serum was designed to operate on a cellular level,” she said as she flipped it open. “We expected it to work in your muscles. Enhanced strength and regeneration. When you came out the same, we all believed it didn’t work.”

She slipped something out of the file and placed it on the coffee table. “What if it did?”

Steve forced his gaze away from hers. It was a photo of him. They’d taken it before he’d gone into the machine.

He wanted to believe they were both seeing things, that this was both in their heads. The reality in which he was crazy was better than the reality that he wasn’t changing. That he wasn’t aging. That he couldn’t die.

Maybe he was the ghost.

“What do I do?” he asked. People would notice soon if they hadn’t already. He was thirty-seven. He looked twenty-five. No one had ever expected him to live this long.

(His childhood self spit blood on the ground and stared defiantly at everyone who said he’d die. He’d told them. His body wasn’t a grave.)

She shook her head, the corner of her lips caught between her teeth.

“Peggy, what do I do?”

“We can make you disappear,” Sousa said, coming to stand behind her. He put his hands on her shoulders. His ring gleamed silver in the lamplight. “It wouldn’t be hard. We’ve done it before.”

“Where would I go?”

You told me not to do it, Buck. You told me it was stupid and that I would miss the life that I had the moment it was gone. You told me you’d do anything to be able to stay in our shitty apartment that never had heat.

It wasn’t hard to pack everything he owned. Most of it fit in one box.

You told me one night that you wanted to run away. Across the border and into Canada. Live in the woods and build a cabin and have fires every night while looking at the stars. You said we could do it. We could be free. I think I was supposed to be asleep because you never mentioned it again. God, I wish we did.

He stood in front of the Barnes’ door for a minute, his hand poised to knock. It fell back to his side and he turned away. It was easier this way.

You were right, Buck. It was stupid and I miss the life I had. Losing you was easier when I thought I would die.

Howard had a facility upstate that he mainly used for storage. There were walking trails and a kitchen larger than his entire apartment and too many beds for Steve to know which one he should take.

The ghosts he’d lived with for years weren’t there. Steve thought it would be easier without the constant reminders. He could build a new life, something far away from the streets that had torn him apart. But they were also where he’d learned to fly.

I had stories to tell you, Buck.

I told you not to die, you asshole.

His entire life, Steve had been running away from death. He’d run too far.

1957.

It wasn’t as bad as he thought it would be, living in Howard’s abandoned warehouse. He had so many, Peggy said, that he had all but forgotten this one existed. They called it the Compound. Peggy still visited, along with a tall, thin man named Jarvis. Steve remembered him from her wedding. They kept him company, and when they couldn’t come, Steve wandered.

Crutch beneath his arm, he walked the miles of trails around the building. There was a freedom he’d never felt in the city. Bucky would’ve loved it here; there were so many stars.

The ghosts of their apartment didn’t follow him, so Steve created his own. The stub of a cigarette in the windows, a pulp novel open on the couch, shaving cream on the bathroom sink.

He tried to figure out what he wanted to do with the rest of forever and wrote a letter.

1963.

Steve watched the news footage of the Kennedy assassination over and over, the engraving of Bucky’s name pressing into his palm.

He still looked twenty-five.

1970.

Peggy told him that Howard had a son. They named him Tony.

Life went on. So it goes, and all that shit. Kurt Vonnegut got it.

1991.

Sometimes, the years passed quickly. Steve painted and read and did his best to not feel guilty when he laughed. He still wasn’t used to the idea that he would forever look and feel twenty-five. Steve figured he never would. (How could he? He was supposed to be dead.)

He kept his ghosts. The letters stayed in the box in the oven. He still wrote them. One every week.

Peggy’s hair was almost entirely silver now. She’d retired from fieldwork years ago but still kept her desk at the office. Sometimes, she brought files and Steve helped her go through them. It helped with the monotony. Steve wasn’t stuck in the Compound, not anymore, but it was safe and never-changing like him.

He went to the closest town once. There was a new war broadcast on all the TVs in the shop windows. Some people stopped on the sidewalk to watch, but most everyone kept walking. It didn’t matter to them. In a string of conflicts, it was just another war.

A man looked at his crutch and Bucky’s tags and thanked him for his service.

Steve’s veins itched. Smoke scratched his throat.

He stared at himself in the glass and watched his hand rise to press against his cheek. Steve wanted it to pass through. It landed, as it always did, on cool skin. Solid. Real. Unending.

He returned to the Compound and his ghosts and held the tags until Bucky’s name was engraved on his skin. Like everything apart from him, it faded.

Peggy was crying when Steve saw her next, ten days before Christmas. Snow fell outside, bitter and cold. It bit into Steve’s skin. The warmth inside burned just as much.

She busied herself in the kitchen, making them cups of tea. Forty-six years had passed and Steve was back in the tiny kitchen of his apartment, watching Winnifred fussing over the kettle, her hands shaking as she tried to keep them busy. Steve cupped his hands around Peggy, smooth skin against wrinkles. She looked up.

“Tell me,” he said.

(“We got a letter,” Winnifred whispered.)

“It’s Howard,” she said. “They say it was a car crash, but I think—he was obsessed with the serum. It’s why we never told him about you, why we never told him you were here, why you’ve never met Tony. He was transporting vials.”

(“Jamie—he—”)

Steve looked at his hands. Small and bird-boned and unmarked by age apart from the callouses built up from his paint brushes and the small scar on his pinky from the jagged edge of a beer bottle.

The serum did kill.

“Is there anything I can do?”

Peggy looked at him. Brown eyes and wrinkles and everything Steve should be but couldn’t. “You’re proof he didn’t die for nothing, Steve. It wasn’t what we thought, but you’re alive. Isn’t that enough?”

2009.

Peggy was in the hospital when Steve first saw her. A woman with dark red hair, long and curly. She walked gingerly, a hand over her side, and looked in both directions before entering Peggy’s room. She looked at Steve with narrowed eyes. They were a deep green. Calculating. Never settling.

“Fury told me I’d find you here,” she said to Peggy, her eyes never once leaving Steve.

“You can trust him,” Peggy said. “I’ve actually wanted you to meet for a while. Natalia, this is Steve Rogers.”

Steve leaned heavily on his crutch. “Pleasure,” he said, offering her the chair. He still didn’t sit. Natalia looked to Peggy instead.

“Odessa was a set-up. But you knew that, didn’t you?” She threw a file onto the bed. “He was there.”

Peggy took the file in her hands, wrinkled and spotted. “I didn’t know.”

Natalia’s nostrils flared. Her lips moved. Steve didn’t make out what she said. She left a minute later, her hand back on her side. Steve looked at Peggy, who stared at the file. Paper spilled over the blankets. The English looked foreign.

“For years now,” Peggy finally said. She didn’t look away from the file. “There’s been a ghost story in the office. It started when I was still director.”

Steve thought of the ghosts he lived with. Self-created, but ghosts nonetheless. They were everywhere.

“There was a rumor in the war that the Germans found a dying American soldier. They saved his life at a cost. He became their greatest weapon.”

Cigarettes in the windows. Shaving cream on the bathroom sink. Letters in the oven. The book had been moved.

“Tell me,” Steve said.

“They called him the Winter Soldier.”

Steve became obsessed. He poured over everything Peggy gave him until it was seared into his memory. There wasn’t much: a date, a hypothesis, a blurry photo of a masked face and the gleam of a metal arm.

When he couldn’t sleep, he painted.

American Soldier.

Steve didn’t dare hope. Death would be better than this ghost story. Steve gave him Bucky’s eyes. He’d finally gotten the color right.

2011.

Steve watched the footage as aliens rained from the sky. Howard's son and Natalia and a handful of others Steve didn’t know fought them off.

(His veins itched. He should’ve been there.)

He hunted for the ghost story. Anything to not be alone in this curse of life.

2012.

Peggy told me a story a few years ago, Steve wrote. His desk was full of old files. A corkboard hung on the wall above, covered in articles about Kennedy’s assassination, scrawled notes, and the blurry photo of the American Soldier.

She said it was a ghost story, but I’ve often found that all ghost stories come from something true. There’s no horror unless it’s possible. An immortal soldier. They never found your body, Buck.

It’s not you. I don’t want it to be you. I know I always said I’d find a way to live. I said I’d face Death and tell him to fuck off. It’s not what I thought it would be. We’re not meant to endure like this.

Years just pass. I used to take everything day by day. I used to be present for everything. I had to.

It’s been almost 70 years, Buck. I hate you for leaving. I hate you for not letting me say goodbye. I hate you for not coming back. I hate that I still love you. You’re a right selfish bastard, you know that, right? This train is endless. There’s no end without you.

Fuck you.

2013.

Steve looked everywhere he went. He wanted to see a flash of metal. He wanted to know that the stories were true. He didn’t want to be alone.

He left a trail of lemon candy.

2014.

There were too many ghosts in the Compound. Too many in New York. Brooklyn was haunted. He moved to Washington D.C. and walked around the memorials, ignoring the pain in his back and the ache in his feet and the burn in his lungs. They meant he was alive. That’s what Bucky always said. God, he’d hated that. He had to hold onto it now.

The sky was purple and the sun hadn’t yet risen. Steve walked around the Reflecting Pool. He still avoided mirrors.

He was alone apart from the man running laps. Steve changed his direction so his right ear faced him. He liked the methodical pounding of his feet. Each time the man passed, they exchanged nods. His name was Sam. He had ghosts, too. His was named Riley.

Steve ran into Natalia again. She went by Natasha, now. He liked her.

He missed Peggy, missed knowing he didn’t have to hide with her, missed that she was from his time, but he enjoyed their company. Sam made him laugh the same way Bucky did, and when Steve earned a rare smile from Natasha, it was like those hot summer days.

He was learning that whatever it was he did in those years before moving, it wasn’t living.

He still looked everywhere he went.

It was a Tuesday afternoon. He and Sam were walking down M street when Steve caught a flash of sun on metal. He blinked. There was a man. He blinked again and he was gone. The crosswalk changed and Sam pulled him along. Steve reached into his pocket and dropped a piece of candy.

Steve started seeing him everywhere. The corner with his favorite deli, the intersection of 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, the monuments. It was always the same. A blink and he was gone. Steve was starting to think the stories were true. He really was a ghost.

It was all over the news. Shield taken over by Hydra. Helicarriers in the Potomac. Natasha had to disappear for a while, but she did so with the promise to stay in touch. She couldn’t say much, despite everything she leaked on the internet to protect them.

In the aftermath of the destruction, Steve stopped seeing him. The American Soldier. The Ghost. That had to mean something, right? To be seen and then not.

He ran out of lemon candy.

Steve tried to forget about it. He tried to focus on everything he had now. He had friends. Sam invited him to live with him. After living alone for so long, Steve accepted at once. It was nice to have a room and place that felt like a home. (He tried not to feel guilty about it. It had been over seventy years. Bucky would want him to be happy.)

Steve told Sam his real age. He explained everything that happened with the serum. If he was going to be alone in living forever, he needed someone else to know.

He wrote two letters. One to Bucky. One to the Ghost.

2015.

Steve turned ninety-seven. Sam threw him a small party. Natasha came, along with her friend Clint. He was one of the people Steve watched save New York from the aliens. When he saw Steve’s hearing aids, he excitedly pointed to his own and signed rapidly.

Steve smiled and remembered nights out on the fire escape. He remembered his and Bucky’s made-up language; their combination of Irish and Yiddish and Sign. Bucky would’ve loved this. He would’ve made fun of Sam’s strange obsession with birds. Steve told him about it in a letter.

2016.

Peggy died.

Of all days, it was a Thursday. Since Peggy’s death, Steve had walked around the monuments every morning. It didn’t matter the pain in his back or the ache in his feet. It didn’t matter if his lungs burned. He walked. He hadn’t gotten sick since 1943. Sometimes, Steve missed it. He missed the fight to stay alive.

Steve always started at the reflecting pool. He liked flirting with the idea of seeing his never changing face. It felt a lot like his youth and running toward a fight. Catching it felt like flying, like wind beneath his skin. He imagined a boy with curly hair and a missing tooth. He imagined a boy with sun-kissed skin and eyes that took a lifetime to color. He imagined a young man who laughed so easily it made Steve believe that was the meaning of life. He imagined cigarettes in the windowsill and shaving cream on the bathroom sink and a pulp novel open on the couch.

He imagined a hand reaching out to pull him up.

The emptiness around him always felt like the sting of scraped skin and the ache of knocked bones.

Steve wasn’t alone that day. He looked up from the concrete to see a man sitting on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Time slowed. Or maybe it stopped. It didn’t matter to Steve which one. He walked forward.

When Steve was twelve, Bucky found a piece of warped glass on the beach. They’d had endless hours of entertainment watching as a tiny shift had the entire world coming into tune. Steve walked forward and the world made sense again.

Steve knew those eyes. He knew the dimple in the chin and the shape of those ears. He saw the hand reaching out. Felt skin brush against skin. It wasn’t real. It couldn’t be real. Bucky was dead. Steve had been surrounded by ghosts for so long that he couldn’t tell the difference anymore.

He kept walking forward, pain in his feet. Bucky looked at him and through him. The hand disappeared.

A ghost.

Steve turned away.

A flash of sunlight on metal had his steps faltering. Steve’s mouth went dry. His stomach dropped and his skin went hot. When he turned, he expected Bucky to be gone. The Soldier, after all, was a ghost. He still sat there. A leather jacket covered the entirety of his left arm apart from a sliver of his wrist. It still caught the rising sun.

Steve made himself keep walking forward. Toward the fight and away from death. Toward the war Bucky told him to stay away from. He should’ve known Steve wouldn’t listen. Steve loved him too much.

Steve knew the curls and the way his chin dipped before he swallowed. He didn’t know the haunted shadows beneath his eyes. Steve was sure he had the same. You didn’t escape death and come out unscathed.

“It’s you,” Steve said.

Bucky looked at him, and this time, their eyes met. Steve knew them. Knew their blue and the precise way to shade them. Knew how much green and grey to mix in. Bucky swallowed. His arm moved as if he wanted to reach out. He shook his head. Blinked. Steve stayed.

“I kept seeing you,” Bucky said. His voice was quiet and rough. Unused. “They kept trying to take you away from me, but I kept remembering you.”

Pain sliced through Steve’s heart. Peggy had said they’d saved him at a cost. His hand wrapped around the tags and he pressed Bucky’s name into his skin. His heart beat loud and heavy beneath his bony chest. Steve climbed the steps.

Bucky put his hand into his pocket and pulled something out. His wrist turned in the same delicate movement Steve remembered. A lemon candy sat in his palm.

“You stopped looking.”

Steve swallowed. “You were a ghost story. You told me to live.”

A smile ghosted over Bucky’s face. There and gone so fast Steve almost thought he imagined it. “Since when do you listen?”

Steve shrugged. “You weren’t there to pull me out.”

Bucky’s hair was longer now, ending just above his shoulders, which were broader. He was different than Steve remembered.

“You’ve changed, Buck.”

Maybe he wasn’t a ghost. Ghosts couldn’t change. They stayed the same as when they died. Never changing. Never moving forward. Stuck.

Bucky looked at him. Steve watched the guilt and pain and confusion flash through his eyes. His jaw shifted minutely. He swallowed. His right hand reached out and touched Steve’s face, the way Steve had done all those years ago. Again, he remembered the way Bucky had laughed. Steve closed his eyes.

Real.

“You haven’t.”

“I told you I wouldn’t die,” Steve whispered. He was the ghost.

He was supposed to have been a phoenix.

Steve’s back hurt and his feet ached. He sat.

I met you again today, Steve wrote. You talked to me. You don’t remember a lot. That’s okay. I can remember for the both of us. You don’t have to be alone anymore.

Maybe this train doesn’t have to be endless.

It took time. For the first time, Steve didn’t care. He had all the time in the world.

2017.

Sam helped him find a place back in Brooklyn. The city was still filled with ghosts, but it felt different. Steve had room for them.

Steve asked Bucky to move back in with him on a Thursday.

The apartment wasn’t big, but it had two bedrooms and a kitchen and a bathroom for Bucky to put his shaving cream. A mirror hung in the entry hall. There were big windows in the living room and soft blankets on the couch. The first time Steve saw Bucky curled up in the sun, his face slack in sleep, he was thrust back in time. They were in their shoebox apartment and Steve’s lungs ached because of the harsh winter, but none of it mattered because the sun shone and Bucky was there.

Steve grabbed a blanket and tucked it around Bucky’s shoulders.

Everything had changed.

Bucky’s left shoulder pained him now. Bands of scars circled around it, reaching like lightning across his chest. Bucky kept his fist clenched when he first told Steve about waking up and trying to get it off.

“It didn’t work, Steve,” Bucky told him, curled up on the couch under a pile of blankets. “Or not the way they wanted it to. I’m not the Soldier they wanted.”

Steve found his hand under the blankets and uncurled it, slotting their fingers together. “I’m not either.”

The nail marks faded from his skin but the pain stayed.

Bucky poked his head out from under the blankets and peered at him. His eyes weren’t as shadowed anymore. “Did you take your medicine?”

Steve smiled and closed his eyes. Nothing had changed.

“What are these?” Bucky asked. Steve looked up from his painting to see Bucky holding a box of Steve’s letters. He couldn’t keep them in the oven anymore, so he’d put them on a shelf. He put his paintbrush down.

“I wrote to you,” Steve said. “From the moment you left, I wrote to you.”

Bucky sat on the couch and opened the box, letting his fingers brush over the paper. Some of it crackled. Sunlight pooled into the apartment. “Can I read them?”

Steve nodded. “They’ve always been yours.”

Bucky kept looking at them. Steve moved away from his canvas and sat beside him. Bucky picked one up and started to read. For hours, there was nothing but the sound of their breathing and the turning of paper.

“Steve? What do you want from me?” Bucky’s fingers traced Steve’s words. His declaration of love. They’d never needed to say it as kids. It was in everything they’d done. The hand reaching out, the laughter, even Bucky’s final words, it was all love. “I can’t give you any more than this.”

Steve looked at him. Bucky’s hands wrung themselves. Steve closed his around them.

(“We got a letter,” Winnifred whispered. “Jamie—he—”)

(“It’s Howard,” Peggy said. “They say it was a car crash.”)

“Just let me love you. That’s all I need. Nothing more.”

Bucky stared at their hands, flesh and silver, bird-boned and unmarked by age. “I’m not who I was before the war, Steve.”

Steve shrugged. “We all got somethin’, Buck. That’s how you know you’re still alive.”

That’s how he knew he was still alive.

And maybe they were older now, and maybe they’d gone through a few things, and maybe death would’ve been easier, but they were here. They were alive. That mattered more than anything.

Bucky fussed with his hair in the mirror. Steve watched him.

They’d had their first sleepover when Steve was seven. They’d tried to stay awake the entire night. They talked and laughed, and Sarah had to tell them to go to bed. The morning would be there, she’d said.

Bucky finished reading his letters, and then read the letters Steve had written to the Ghost. They were the same person.

When they got older, they graduated from reading ghost stories to making them up. Steve was never very good at it, but he tried just as hard as Bucky. Haunted houses and the undead and hearts in the floor. They always fell asleep before the first signs of dawn streaked the sky.

Bucky slipped his fingers between Steve’s. They couldn’t offer each other more than that, but it was enough. Steve touched Bucky’s face, and Bucky threw his head back in laughter. Steve learned there was a difference between being a ghost and being a ghost story.

They both had nightmares. Steve sometimes still tasted the tang of smoke. Bucky dreamed of ten words and electricity. Some nights, they both went to the couch. They sat until they could talk and talk until they could laugh. Bucky offered Steve lemon candy and Steve placed it on his tongue, letting it fill his mouth with the promises of summer days and warmth and happiness.

They made up new stories. Ways to fill their future.

They watched the sun rise.